Knee

Knee Overview

A Guide To Your Knee:

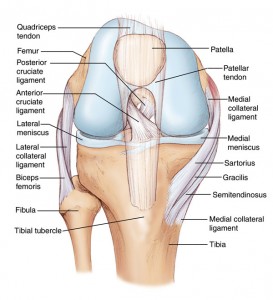

The knee is composed of bone, articular cartilage, meniscal cartilage, and ligaments and tendons as shown below. The structural integrity of these structures along with the alignment of the knee determines the health of the knee joint. Abnormalities of some or all of these entities are responsible for all knee problems. With available technology we can specifically address each of them, singly or in combination, to treat knee disorders.

Articular Cartilage:

Articular cartilage is the super slippery smooth substance that coats bones within joints and allows them to move without almost no friction or wear. Articular cartilage rubbing against articular cartilage in a joint is ten times more slippery than ice against ice. In the knee, it is three to four millimeters thick. It can become worn and thin and develop holes such that bone is exposed underneath it. This causes increased friction, inflammation, and pain. In early stages, this is called chondromalacia. In advanced stages, it is called arthritis. It can occur anywhere on the femoral condyles, tibial plateaus, or patella (kneecap).

Depending on the severity and location of the cartilage damage, cartilage damage can be treated with PRP injections and with the surgical procedures called microfracture or autologous cartilage implantation.

Bone:

Bone provides structure to the knee joint and the entire body. Sometimes there are holes in the bones of the knee, as well as the overlying cartilage. This is called osteochondritis dissecans, or OCD, for short.

Meniscal Cartilage:

The two menisci in the knee are made of “fibrocartilage.” This is a hybrid tissue that is part articular cartilage and part fibrous tissue (which is what scar tissue is made of). There is a medial, or inner, meniscus and a lateral, or outer, meniscus. They are wedge-shaped, i.e. triangular in cross-section. Each is about three to four centimeters in length and width. Their purpose is to cushion the knee and preserve and protect the articular cartilage. When they tear they cause pain and must be repaired (meniscal repair) or removed (meniscectomy). If a small portion of the meniscus is removed, say one third or so, the long-term prognosis is excellent. If a majority of the meniscus needs to be removed some, but not all, patients will develop damage to the articular cartilage and arthritis, as described above. This process can occur quickly or very slowly over decades. When it does we can often transplant a cadaver meniscus to alleviate pain and arrest the progress of the arthritis.

Ligaments:

There are two cruciate (crossing) and two collateral (on the side) ligaments that hold the knee together. The two collateral ligaments are the medial collateral, or MCL, (on the inside of the knee) and lateral collateral, or LCL, (on the outer side of the knee). These collateral ligaments lie outside the joint and cannot be seen arthroscopically. The MCL usually heals on its own when injured and generally does not require repair. The LCL does need reconstruction when injured but it is extremely rare for it to be torn. The posterior cruciate ligament PCL does lie within the knee. It often heals when injured. But even when it tears and does not heal, if there are no other ligament tears in the knee, it is usually not necessary to repair the PCL. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) also lies within the knee. It tears frequently and does not heal when it tears. Surgical reconstruction is indicated for most patients, the results of which are excellent.

Patellar and Quadriceps Tendons:

Tendons connect muscles (which move joints) to bones. In the knee, the quadriceps tendon connects the quadriceps muscle to the top of the patella (or kneecap), and the patellar tendon then connects the bottom of the patella to the tibia. These structures serve to straighten the knee from a bent or flexed position. Patellar tendinitis (inflammation) is among the most common of knee problems. Quadriceps tendinitis is also common and usually occurs in people over 40. The rupture of these tendons requires surgical repair.

Alignment:

A line drawn from the center of the hip to the center of the ankle when a person is standing should pass through the center of the knee. If this line passes significantly to either side there is said to be malalignment. “Bowlegged” alignment is called “varus.” “Knock-kneed” alignment is called “valgus.” Abnormal varus is ten times more common than abnormal valgus. The angle formed by the hip-knee and knee-ankle lines is called the mechanical axis. Patients with varus knees frequently develop arthritis in the medial side of their knee after cartilage injury. This can often be corrected with ACI, MF, and MAT but only if the malalignment is also corrected by HTO.